Our favorite meat cleaver is the Masui AUS8 Stainless Meat Cleaver 180mm. It is durable, easy to hold, and highly capable of handling any small butchering tasks.

How to Use a Meat Cleaver

If you’ve only seen meat cleavers being brandished in cartoons or kung fu movies, they can seem a bit intimidating. But they’re actually not all that hard to use—as long as you do so correctly.Historically, the meat cleaver was a brutish tool. Designed to hew through bone and sinew with a single well-placed cut, the traditional meat cleaver derived its chopping power more from blunt force than from razor-sharp precision and required some strength and experience to be wielded successfully. These days, even professional butchers don’t use cleavers; for hacking through ribs and other dense bones, the three prominent Boston-area butcher shops we consulted (Savenor’s, T.F. Kinnealey & Co., and M.F. Dulock Pasture-Raised Meats) instead use handsaws or band saws, which cut more cleanly and with far less effort.

If butchers don’t need these archaic knives, do home cooks? For most people, the answer is no. That’s because there are relatively few tasks for which a cleaver is a better choice than a chef’s knife. But for those few tasks, there’s no more perfect tool. A cleaver is made for rough use—its heft and size make it ideal for jobs that might otherwise damage or wear down your chef’s knife, allowing you to chop through whole chickens, whole lobsters, or large squashes with impunity. If you make a lot of stock, for example, a cleaver is a solid investment, as it allows you to expose more of the bone and meat to the water for better flavor extraction. Once you have a cleaver, you might find it handy for other tasks too: mincing raw meat, crushing garlic, bruising lemongrass, cracking open coconuts, and chopping cooked bone-in meat into bite-size pieces. The flat of the blade can even be used like a bench scraper to scoop up chopped items or to flatten and tenderize cutlets.

For this review, we examined models that ran the gamut from heavy, axe-shaped, Western-style cleavers to models that more closely resembled Chinese cleavers—lighter-weight knives with thinner, more rectangular blades—to hybrid styles that combined attributes from both. And we asked professional cooks and butchers to help us evaluate them.

What to Look For

- Medium Weight: We preferred cleavers that weighed 14 or 15 ounces. These provided enough force to chop bone-in meat and butternut squash but were still light enough to direct effortlessly, allowing us to hit the exact spot we wanted every time.

- Good Balance: We preferred knives whose weight was evenly balanced between the blade and the handle, as we found these easier and more comfortable to wield for long periods.

- Long, Tall, Slightly Curved Blades: We liked cleavers with blades that were between 6.75 and 7.25 inches long, as these gave us plenty of room to strike larger pieces of chicken or bisect whole butternut squash. Blades that were at least 3 inches tall helped guide the knife straight down through bigger items such as the butternut squash and duck and provided larger surface areas for scooping up chopped food. And we had a small preference for slightly curved blades rather than straight-edged ones; the curved blades allow users to rock back and forth to finish cuts that haven’t been delivered with enough force to get through the food.

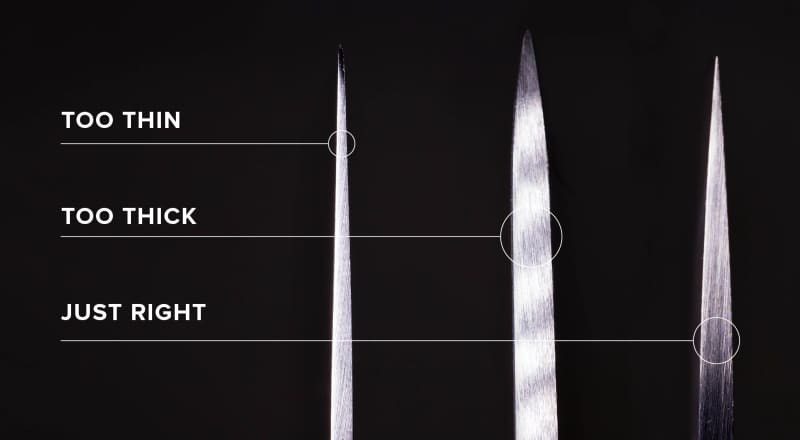

- Relatively Thin, Sharp Blades: The cleavers we liked best struck a happy medium between the power and durability of the thick Western-style cleavers and the precision and agility of the thinner Chinese-style models. Our top models had fairly thick spines that gave the knives enough heft and downward force to chop easily through skin and bone but still felt sharp and highly nimble, thanks to blades that were otherwise moderately thin and ground to acute 15- to 18-degree angles. These blades did chip slightly more readily than thicker ones, but that isn't a deal breaker in a knife intended for hard use.

- Long, Broad, Grippy Handles: We liked handles measuring at least 4.75 inches in length, as these accommodated both small and large hands easily. And we preferred handles that were neither so thick that we had a hard time keeping our fingers around them nor so narrow that other testers felt they had to clench them tightly to control them: A circumference of 3.25 inches was about right for most people. We generally preferred handles that were made with wood or rubbery plastics, which helped us keep our grip on the cleavers—an important consideration when combining big knives with slippery raw meat. That said, both wood handles and more conventional plastic handles sometimes loosened or even cracked during use—a tendency that diminished their durability.

What to Avoid

- Very Heavy or Very Lightweight Knives: The cooks and butchers who tested these knives agreed: The more traditional Western-style cleavers were overkill for the tasks we asked of them. These heavy models clocked in at more than a pound—a weight that conferred power but fatigued many testers’ arms during extended use. And while lighter cleavers weighing 10 or 11 ounces required less practice to use competently, they required more effort than our favorites to drive through the chicken bones.

- Skewed Balance: The bulk of the weight in most traditional Western-style cleavers is concentrated toward the front of the blade. In theory, this intentional imbalance naturally encourages the knife to fall forward and down when chopping. In practice, we found that this made the knives unwieldy and hard to aim and control, leading to uneven, less presentation-worthy slices of roast duck.

- Blades That Were Too Short or Too Long: Cleavers with blades shorter than 6.75 inches in length felt stumpy and toy-like, incapable of bisecting wide butternut squash bulbs with a single cut. On the flip side, blades that were longer than 7.25 inches did a good job of handling squash but felt ungainly with smaller chicken parts. We also didn’t love blades that were short in height, as these were a little trickier to direct through tall butternut squash and whole chickens and duck.

- Thick Blades: Traditional Western-style cleaver blades are thick from spine to edge and are sharpened to an angle of more than 20 degrees on each side. These characteristics were designed to give the blades extra power and longevity; the more metal behind the edge, the stronger and less vulnerable to dulling or chipping it will be. Indeed, these knives seemed impervious to damage, surviving testing with no obvious dents or dings. Unfortunately, the characteristics that made the blades strong also made them less enjoyable to use; while a quick touch made it clear that the edges were plenty sharp, they rarely felt that way in action. Those thick, wedge-shaped blades effectively muscled their way through food, cracking and tearing butternut squash instead of slicing through it in a controlled, even manner.

- Ultrathin Blades: The Chinese-style cleavers we tested had very thin blades sharpened to more acute angles of 15 to 18 degrees. As a result, they felt keen, agile, and precise in our hands. But they were also less durable, their edges collecting tiny but visible chips during testing. While this might be a deal breaker in a chef’s knife, we didn’t mind a few minor dings in our cleavers—they’re practically inevitable when you’re chopping through hard bone. Still, we’d prefer a blade that could take a reasonable amount of abuse.

- Short, Slippery, Too-Thick, or Too-Thin Handles: Handles shorter than 4.75 inches didn’t leave enough room for large hands. Handles made from slick materials were harder to grip, especially when dealing with slippery raw proteins. And handles that were too thick were harder for small-handed testers to hold; if handles were too narrow, even smaller-handed testers had to clench them tightly to control them.

The Tests:

- Chop 4 pounds of chicken wings

- Chop 5 pounds of chicken leg quarters

- Chop butternut squash into quarters

- Break down a whole roast duck and chop it into serving-size pieces

- Ask five test cooks of different hand sizes, dominant hands, and levels of butchering experience to chop 1 pound of chicken parts with each knife

- Ask two professional butchers to evaluate and test each knife

How We Rated:

- Performance: We rated each cleaver on how easily and neatly it chopped through raw chicken wings and leg quarters, a whole roast duck, and a butternut squash.

- Ease of Use: We rated each cleaver on how easy it was to maneuver—how heavy it was and how well balanced.

- Blade: We rated each cleaver on the design of its blade, characterized by its height, curvature, angle, and thickness at spine and edge.

- Handle: We rated each cleaver on the design of its handle, as determined by its length, width, affordance, and grippiness.

- Durability: We rated each cleaver on how well it withstood damage (chipping or dulling of the blade and cracking or loosening of the handle).

Buy at Williams Sonoma

Buy at Williams Sonoma