Our recipes often call for dry white wine. Its crisp acidity and lightly fruity flavor add depth to everything from pan sauces and pasta to risotto and steamed mussels. The problem? Standard wine bottles are 750 milliliters, and our recipes rarely call for more than 1 cup (roughly 235 milliliters) of wine. That leaves us with most of a bottle to finish in a matter of days. Dry vermouth, which can be substituted for white wine in equal amounts in recipes, is a convenient alternative. Like Marsala and sherry, vermouth is wine that’s been fortified with a high-proof alcohol (often brandy), which raises its alcohol content and allows to it be stored in the refrigerator for weeks or even months after opening. Although vermouth fell out of favor with Americans during the Mad Men era of bone-dry martinis, its availability and popularity are on the rise. Small manufacturers have popped up in San Francisco and Brooklyn, and bars are responding by featuring vermouth in cocktails. In the past few years, products from European manufacturers such as Noilly Prat and Dolin—which had previously been hard to find in the United States—have become widely available.

Now that we have more options, which bottle should we be buying? We found eight dry vermouths, that are available nationally. Our lineup included vermouths produced in Italy, France, and California, with 15 to 18 percent alcohol by volume (ABV). We first sampled them plain, served chilled. Then, to see how they fared in a cooked application, we used them in place of white wine in simple Parmesan risotto.

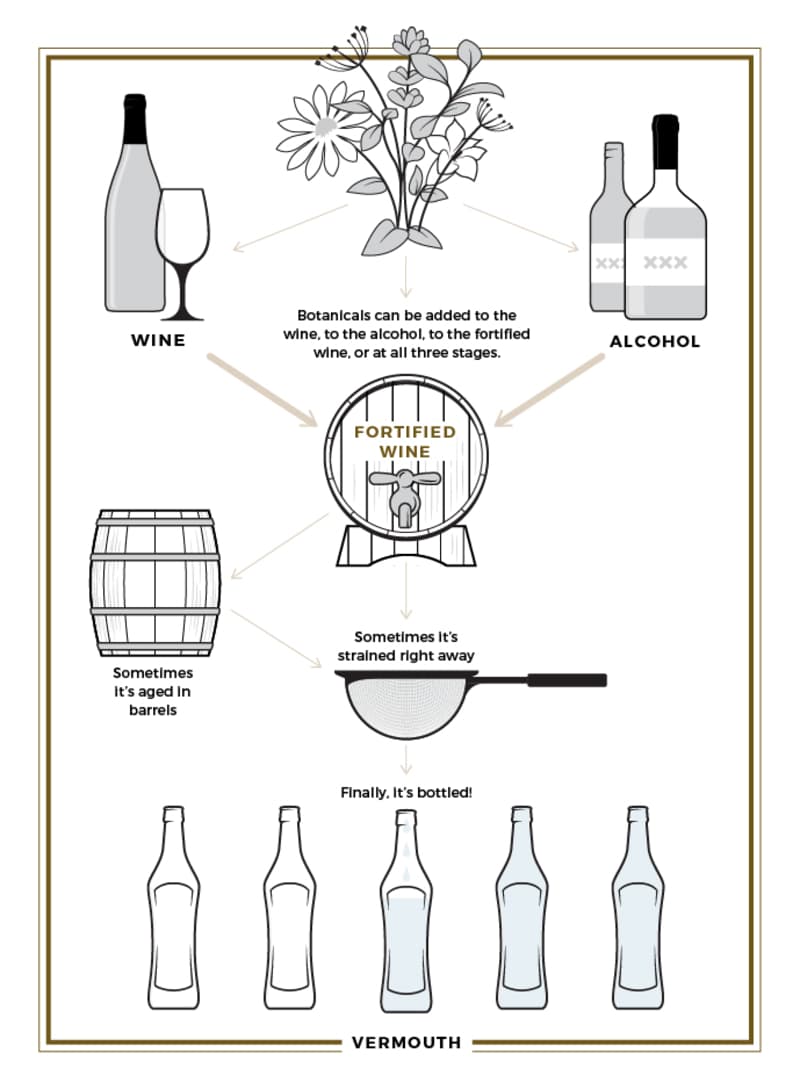

First, a little demystifying. In addition to being fortified, dry vermouth is infused with botanicals. That exotic-sounding term is a catchall for any ingredient sourced from a plant, including leaves, roots, flowers, seeds, herbs, and spices. Those botanicals can be added in a variety of ways: to the base wine, to the high-alcohol spirit, after the alcohol is added to the wine, or at multiple steps in the process. Vermouth is sometimes aged in barrels, which is intended to impart an oaky, vanilla-y quality and can allow harsh flavors or sharp tannins to mellow. But none of that is required. The Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, which supervises alcohol production in the United States, simply stipulates that vermouth must be made from grape wine with alcohol added and have the “taste, aroma, and characteristics generally attributed to vermouth.”

When we evaluated the dry vermouths, they fell into two broad groups. Some were intensely flavored, with lots of warm spice and “funky,” almost “medicinal” hits of “pine,” “menthol,” and “anise.” These risked dominating milder flavors in simple applications such as risotto. We preferred products that were still “aromatic” and “more interesting” than a run-of-the-mill white wine but that tasted more like green herbs and citrus than winter spices. In risotto, our favorites added “a slight floral note” that enhanced the dish but didn’t overwhelm the mild flavors of sautéed onion and nutty Parmesan cheese. The alcohol content of the wines didn’t have a bearing on our ranking, but we did prefer dry vermouths that weren’t overly sweet.

Some of the producers in our lineup claim to have been following the same recipe for nearly 200 years, and all the companies guard their methods closely. At best, they revealed a handful of botanicals or the type of wine. But we knew that designing a vermouth recipe was about more than just choosing a wine and a selection of herbs and spices. After all, the various parts of a single herb can taste quite different: Think about the difference between coriander seed, cilantro leaves, and cilantro stems, which are all from the same plant. One company told us that it uses only dried herbs to help control for seasonal variation in plants. Kristin Wemer, a beverage architect at the beverage development company Flavorman, explained another option: what professionals in the food and beverage industry refer to as “flavors.” These are potent liquids that have been distilled or extracted from plants or created from a chemical source. According to Wemer, these flavors are used in very small amounts, making up 0.5 to 2 percent of the vermouth. As with dried botanicals, using liquid flavors makes it easier to control the flavor from batch to batch.

With manufacturers keeping mum, we crunched the numbers on our taste test results and came to a clear conclusion. Dolin Dry Vermouth de Chambéry, a French product that has only recently become widely available in the United States, earned top marks in our plain tasting thanks to its “crisp” acidity and “green notes” of fruit, citrus, and mint. It also produced a risotto that had “distinctive” herbal and peppery notes. It’s the best option for people who want to cook with vermouth and might occasionally drink it as an aperitif or mix it into cocktails. If you use dry vermouth primarily for cooking, we have a Best Buy: Gallo, from California, was slightly sweeter (but not cloying) and had more subtle botanicals. Risotto made with it tasted pleasantly “mild” and “bright,” with a “slight floral note.” It costs less than we typically spend on a bottle of wine for cooking—and it will last for several weeks in the refrigerator. Cheers to that.

- Taste plain, served chilled

- Taste as a 1-to-1 substitute for white wine in Parmesan risotto, served hot

- Crisp, lightly sweet wine flavor

- Bright, fresh herbal flavor

- Variety and intensity of botanicals complement rather than overwhelm food