When we want big chocolate flavor in everything from cookies and cakes to puddings and pies, we turn to cocoa powder. It has a higher proportion of flavorful cocoa solids than any other form of chocolate, so ounce for ounce, it tastes more intensely chocolaty. It's made in two styles—Dutch-processed and natural—and there's fierce debate in the baking world about which is best. Both styles have staunch supporters who are convinced that using the wrong type will ruin a dessert. For years, we also viewed Dutched and natural cocoa powders as distinctly different products. But when we last evaluated cocoa powder, something surprising happened: A natural powder won, a Dutched powder came in second, and the rest of the lineup was a jumble.

In the years since, we've remained curious about cocoa powder. Some of our test cooks prefer the dark color of Dutched powder and swear that it has richer, deeper chocolate flavor to match. Are they onto something? Is choosing between Dutched and natural the most important decision you can make when buying cocoa powder, or is there more to it than that?

To find out, we sampled eight nationally available cocoa powders (priced from $0.34 to $1.70 per ounce): four Dutched and four natural. To zero in on how much Dutch processing matters, we carefully selected recipes for testing: two different sheet cake recipes—one that calls for natural cocoa powder and another that uses Dutched—and a cookie recipe that doesn't specify which style to use.

The results were mixed. While some desserts were simply acceptable, others were excellent. The good-enough cakes and cookies were tall and “airy” with a “crumbly” structure but a little “dry.” Across the board, we preferred “moist” and “fudgy” desserts. Our favorite cakes had a “plush” texture, and cookies toed the line between chewy and tender. As for flavor, samples ranged from “mild” and “slightly fruity” to “intense,” “complex,” and “earthy,” with the slight bitterness of good espresso or dark chocolate. Why had some desserts been dry, mild, and lean, while others were so rich, flavorful, and decadent?

From Pod to Powder

Cocoa powder—and all real chocolate—starts with cacao pods, the fruit of the tropical evergreen tree Theobroma cacao. Each pod contains between 20 and 50 beans (also called seeds). The beans generally taste bitter and are surrounded by a fruity-tasting, milky-white pulp, according to Gregory Ziegler, a chocolate expert and professor of food science at Penn State University. The beans are fermented, a critical process that develops their dark brown color, before being roasted. The fermented beans are either roasted whole or are shelled and roasted as nibs. Next, the nibs are ground into a paste called chocolate liquor, which contains a mix of cocoa solids and cocoa butter. Some of the chocolate liquor is used to make candy and chocolate products. The rest is pressed to remove most of the cocoa butter, which is also used to make chocolate. The cocoa solids that remain are ground into small particles and become cocoa powder.

The Journey from Pod to Powder

To deliver rich-tasting cocoa powder, producers must perfect every step of the process.

Dutching Process

An alkalizing agent such as potassium carbonate or sodium carbonate is added to the nibs, the cocoa liquor, or the final pressed powder. This optional step darkens the powder’s color and mellows its astringent notes.

- Harvest Pods: Football-shaped pods are collected from tropical cacao trees. Each pod contains from 20 to 50 beans (seeds), which are surrounded by fruity pulp.

- Dry Beans: Cacao beans are fermented for two to nine days and then dried for up to several weeks before being bagged and sent to processing facilities.

- Roast Beans or Nibs: Cacao beans are either roasted whole and then shelled or shelled first, leaving just the meaty centers—the nibs—to roast.

- Grind Powder: The roasted nibs are ground into a paste called chocolate liquor, which is pressed to extract cocoa butter. The remainder is then dried and ground into a powder.

In the 19th century, a Dutch chemist and chocolatier named Conrad Van Houten developed an optional step for the above process, known as Dutching, Dutch processing, or alkalizing. Chocolate is naturally slightly acidic, and so is cocoa powder. Treating the cocoa with an alkalizing agent neutralizes the acid, raising the powder's pH from about 5 to about 7. Natural cocoa powder is usually sandy brown with a reddish tint and tastes bright and fruity; Dutch processing darkens the color to velvety brown or near-black and mellows the cocoa's more astringent notes so that its deeper, earthy notes come to the forefront.

Dutching is not a one-size-fits-all process. Ziegler told us that manufacturers use a variety of alkalizing agents, such as potassium carbonate or sodium carbonate. They can also adjust the temperature and time of the process and may opt to alkalize the nibs, the cocoa liquor, or the final pressed powder.

Given the potential variation in processing, we were curious about how our powders compared with each other, so we asked an independent laboratory to measure the pH of each cocoa. The lab reported that the pH of the natural powders ranged from 5.36 to 5.73 and the pH of the Dutched powders ranged from 6.88 to 7.90. It doesn't sound like much, but one point indicates a tenfold difference in acidity.

When we reviewed the results of our recipe tests, we saw that some trends fell in line with the Dutched versus natural division. The more acidic natural powders produced some of the tallest, airiest, and crumbliest cookies and cakes. On the other hand, most of the Dutched powders produced baked goods that hadn't risen quite as tall. This makes sense: Baking soda, a common chemical leavener that was in all three of the recipes we tested, releases carbon dioxide bubbles when it reacts with acid and moisture; this is one of the reasons that doughs and batters rise in the oven. The acidity level affected how our cocoa powders interacted with the baking soda and seemed to have played a role in how high our baked goods rose.

In general, the tall, airy cakes and cookies made with natural cocoa powder were perceived as much drier. Our tasters preferred the fudgier, moister desserts made with less-acidic Dutched powders. In fact, a Dutch-processed cocoa powder won every tasting—even when used in a recipe that was specifically designed using natural cocoa powder—and Dutched products took the top three spots overall. But one Dutched powder consistently landed at the bottom of the rankings; baked goods made with it were slightly dry instead of tender and rich. Dutching is clearly an important variable, but it wasn't the whole story.

Fat Is Another Major Factor

There's another big divide in the world of cocoa powder: fat content. When the cocoa liquor is pressed, some cocoa butter remains with the solids, so commercial cocoa powders generally contain between 10 and 24 percent fat. While that full range is technically achievable, cocoa powders don't run the full spectrum. Instead, they're manufactured in two levels: low fat and high fat. An independent lab analyzed the samples and reported that three products in our lineup contained about 11 to 12 percent fat; the rest had nearly double that, about 20 to 22 percent.

Suddenly, things started to come into focus. Most of those high-fat powders scored high in our tastings. Why? Fat adds richness and flavor. It can also help ensure that cookies and cakes bake up moist and tender. The flip side is that desserts made with the low-fat powders, though still acceptable, tended to be dry. The only low-fat cocoa powder to land in the top half of our rankings was Hershey's, which may owe its high score to its familiar flavor. Our other favorites contained at least 20 percent fat, for rich, moist, flavorful cakes and cookies.

The Opposite of Fat Is . . . Starch?

Baking with a low-fat cocoa powder means risking dry baked goods—but not just because fat adds richness and helps prevent baked goods from drying out. Starch is a natural component of all chocolate and cocoa powder, and the less fat cocoa powder has, the more starch it contains. These starches are very absorbent; they're able to soak up 100 percent of their weight in moisture. By comparison, flour can absorb 60 percent of its weight. Like excess flour in a recipe, the extra cocoa starch present in low-fat powders traps moisture and makes for dry cakes and cookies. It's especially noticeable when recipes call for a high ratio of cocoa powder to flour, as with one of the chocolate sheet cakes we made.

To isolate the role of starch, we performed a simple experiment with all eight cocoas. We whisked together precise amounts of cocoa powder and water, transferred the slurries to bags and vacuum-sealed them, and heated the mixtures in a sous vide water bath to exactly 180 degrees, the temperature at which the starches in cocoa powder gel, or thicken. The differences were striking. Some were very firm and bouncy, like a memory foam pillow, and others were almost runny.

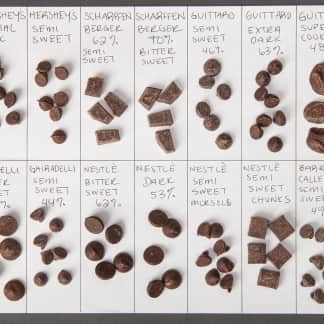

Of course, none of our desserts had been liquid-y or pillowy, but the results lined up nearly perfectly with the textural differences we'd noticed in the cookies and cakes. The cocoa powders that were the firmest in our experiment had lots of moisture-absorbing starch and made tall, airy cakes that tended to be dry; those that produced the runnier slurries had less starch and resulted in moist, fudgy cakes. The pattern was even more evident when we looked at the cookies. Using high-starch powders gave us cookies that rose and had crumbly, cakey textures. Cookies made with low-starch powders spread more, and the available moisture in the dough helped keep them chewy and fudgy. The difference in how much the cookies spread was dramatic. The cookies with the most starch averaged about 3.2 inches in diameter, compared with almost 3.8 inches for those with the least amount of starch—a difference of more than ½ inch. That's a big variation for a chocolate sugar cookie.

Buying the Best Cocoa Powder

By the end of testing, we realized that the old Dutched versus natural debate wasn't wrong but it also wasn't the whole story. The performance of cocoa powder is determined by a complex system of factors including pH, fat, and starch content. For moist and tender baked goods, we recommend buying a Dutch-processed cocoa powder that's high in fat and therefore low in moisture-absorbing starch. (If the nutrition label is all you have to go by, seek out a product with at least 1 gram of fat per 5-gram serving.)

Our top three scorers fell into this category. Each produced “moist” and “fudgy” cakes and cookies that struck the right balance between “chewy” and “tender.” The best of the bunch was our former runner-up (and longtime favorite Dutched product), Droste Cacao ($9.99 for 8.8 ounces), which has the right combination of factors to ensure decadent chocolate desserts with perfectly moist textures and the “sophisticated,” “complex” flavors of good espresso and fancy chocolate. It's well worth seeking out.

- Bake in Chocolate Sugar Cookies, which doesn't specify Dutched or natural cocoa powder, then sample in blind tasting

- Bake in Chocolate Sheet Cake, which calls for Dutched cocoa powder, then sample in blind tasting

- Bake in Midnight Cake, which calls for natural cocoa powder, then sample in blind tasting

- Send samples to independent lab for analysis of pH (a measure of acidity) and fat content

- Cook cocoa powder slurry in sous vide water bath to exactly 180 degrees, the temperature at which starches in cocoa powder gel

- Dutch-processed, or treated with an alkali solution, which mellows the powder's astringency, for a richer and earthier chocolate flavor

- Lower acidity level, so the reaction with baking soda produces baked goods that tend to be moist and fudgy instead of tall and crumbly

- Contains at least 20 percent fat (or a minimum of 1 gram per serving), for baked goods that are rich, flavorful, and less prone to dryness

- High fat content, which correlates with less moisture-absorbing starch, so that baked goods are moist, fudgy, and less likely to taste dry