The best gyuto are easy to hold, nimble, and ultrasharp. We have two top options. One of the lightest knives we tested, the Hitohira FJ 210mm Gyuto VG10 Ho is especially easy to wield for long periods. It has a comfortable Japanese-style wood handle, and its stainless-steel blade is incredibly sharp. We also loved the Masamoto Sohonten VG Gyuto 8.2". Testers liked its solid, heavier profile and smooth, Western-style plastic handle; it’s just as sharp as the Hitohira and can be used by lefties more easily. Our Best Buy is the Kanetsugu AUS-8A Stainless Gyuto 210mm. This entry-level gyuto lacks the beauty and refinement of our top options but is still sharp, agile, and easy to hold, performing well at a fraction of our favorites’ prices.

The gyuto (pronounced “GYEW-toh”) is best described as the Japanese version of a Western-style chef’s knife. It was developed in the 1870s, during the Meiji Restoration. Japan had recently ended its policy of isolationism and had opened its borders to the West for the first time in 250 years. Fearful of being left behind in the global race for power, Japan began a process of industrialization and modernization, adopting Western ideas at a rapid clip. Western influence could suddenly be seen in every aspect of Japanese life, extending even to the foods people began to eat.

Roughly translated, the word “gyuto” means “cow sword” (gyu = cow/beef, to = sword). Prior to the Meiji Restoration, beef was considered taboo in Japanese society. But as Josh Donald of Bernal Cutlery explains in Sharp: The Definitive Guide to Knives, Knife Care, and Cutting Techniques (2018), this changed under Western influence. In an effort to emulate their more modern, industrialized Western neighbors, Japanese people began eating beef, hoping it would give them the power they felt they lacked. You could say that the gyuto was developed to slice that beef—after all, Japanese cutlery is more specialized and task-specific than Western-style cutlery, with dedicated knives for cutting vegetables (usuba and nakiri), filleting and breaking down fish (deba), or slicing sashimi (yanagi). But as Donald explains, the reference to beef in the word “gyuto” is probably more metaphorical than literal: “[It] was named and marketed to evoke brawn and to answer that national yearning for muscularity and strength” that beef (and the Westerners who ate it) connoted.

In practice, the gyuto is probably the closest thing to an all-purpose knife that you can find within Japanese cutlery.

How Is a Gyuto Different from a Western-Style Chef’s Knife?

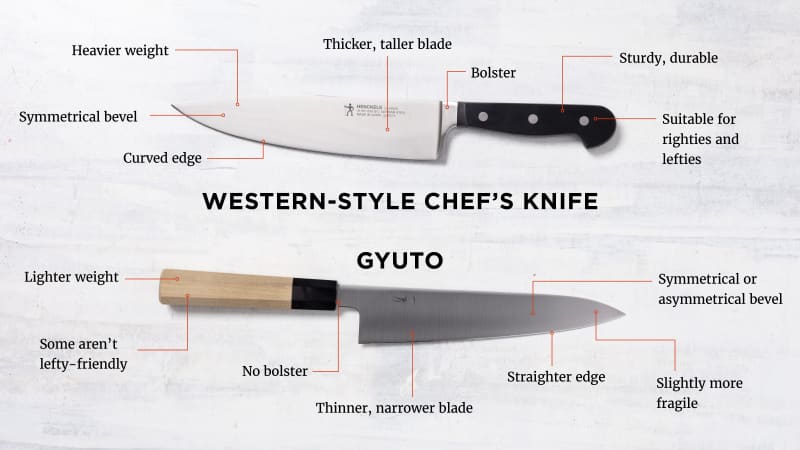

While the gyuto takes its inspiration from the Western-style chef’s knife, there are critical differences between the two knives. The line between Western and Japanese knives has blurred somewhat over the last few decades, but certain distinctions remain.

- Weight: Gyuto (the noun is both singular and plural) are generally lighter than Western-style chef’s knives. The knives in our lineup ranged from about 3 to about 6 ounces, compared with about 4 to 9 ounces in our chef’s knife lineup.

- Blade Design: Gyuto blades are typically thinner from spine to edge and narrower in shape than Western-style chef’s knives. Like most Japanese knives, gyuto lack a bolster—the thick band of metal between the handle and the main section of the blade that Western-style chef’s knives traditionally have. And the edge of the gyuto blade runs in a relatively straight line, whereas Western-style chef’s knife edges are often more curved.

- Blade Material: Gyuto blades are usually made from harder steels than Western-style chef’s knives. The gyuto in our lineup have Rockwell hardness ratings (the standard measurement of material hardness, with higher numbers indicating harder materials) ranging from 58 to 65. By contrast, the Western-style chef’s knives we’ve tested have Rockwell hardness ratings of about 55 to 58.

- Blade and Edge Shape: Both gyuto and Western-style chef’s knife blades are double beveled, meaning that the edge of the blade is ground at an angle on both sides. But the bevel in many gyuto blades is asymmetrical, not symmetrical, as it is with Western-style chef’s knives. Instead of being cut to the same angle, the two sides of a gyuto bevel are often cut at different angles, with the inner angle (the angle closer to the center of the cutting board, which is usually the left-hand angle) being smaller and steeper. With gyuto, the level of asymmetry is expressed in terms of a ratio: 70/30, 80/20, and even 90/10 bevels are possible. The bigger the ratio, the greater the asymmetry. The faces of the gyuto blade—the vertical surfaces extending upward from the bevel—can also be ground at asymmetrical angles. Historically, this asymmetry was used to make the gyuto cut more precisely. And, as Donald told us, it helps the blade hug the food more closely so that you can make very fine, even slices instead of wedging into the food as you might with a symmetrical double-beveled knife.

There are two important consequences of these design differences.

- Gyuto are a bit more fragile. Because gyuto blades are thinner and made from harder metal, they’re less forgiving and can chip easily. Consequently, you need to use them slightly differently than you might a Western-style chef’s knife. Avoid moving the blade laterally (from side to side) or making cuts with a lot of downward force, as either action can make the blade chip or crack. This means no scraping, no twisting, no cutting through frozen foods or bone, no rocking the blade to mince herbs, and no cutting dense foods such as butternut squash, since your blade can wiggle or land on the board too heavily during these tasks and become damaged. Instead, the gyuto is best for tasks where you can use simple push or pull cuts to slice or dice.

- Lefties may struggle with some gyuto. Asymmetrical gyuto blades are typically produced for righties, with a larger edge angle on the right side of the blade. This means that more force is directed toward the left as you cut, steering the blade in that direction. Righties usually won’t notice this at all because this movement mimics the natural drift of their hands and knife; that leftward force curves the blade inward slightly, helping the knife snuggle up to the food as it cuts. But as Kei Kawamoto-Kales of Korin told us, lefties using some right-handed gyuto may find themselves fighting that leftward force a bit while they cut. For them, the knife will seem to kick outward on certain tasks, not inward, making it feel hard to control. Knives and experiences vary, however. Some of our lefty testers had more trouble with certain asymmetrical-bevel knives than others, and other testers didn’t notice a problem with some knives at all. Fortunately, our lefty testers were united on the gyuto they found easiest to use; it’s one of our co-winners.

Why You Should Get a Gyuto

At their best, gyuto are extremely sharp and capable, making for exceptionally keen, agile cutting. And gyuto’s light weight means that they are incredibly easy to wield, even for long periods. Both righties and lefties were impressed by the knives in our lineup. “I feel like they’re actually making me cut better,” one tester said. If you’re willing to be a little more protective of your knife, a gyuto can be a superb option for your main blade.

What to Consider

For this review, we tested gyuto with 210-millimeter (8.2-inch) blades, the size we’ve found to be best for most home cooks. There were no duds; we recommend every knife we tested, many of them highly. Ultimately, our rankings came down to very slight distinctions in sharpness, performance, and comfort. As with most high-quality knives, what’s best for you depends on a few points of mostly personal preference.

- Stainless Steel versus Carbon Steel: Stainless steel alloys (metal combinations) are less likely to rust, and so they are easier to care for than carbon-steel alloys, which must be wiped dry from time to time during use to prevent rust from forming. Proponents of carbon-steel knives say that their blades are easier to hone and sharpen to a fine edge and that they keep that fine edge longer. Many people prefer the feel of carbon-steel knives and enjoy both the care required and the way the blade’s appearance changes over time, reflecting years of use. Still, the exact characteristics of any type of steel depend not only on the the specific alloy that’s used but also on a host of other factors, including the way it’s forged and the temperature at which the metal is treated. Some carbon-steel knives are softer or tougher than others, and some stainless knives take edges better than some carbon-steel knives.

- Western-Style versus Traditional Japanese Handles: Japanese knives can have two different types of handles. Western-style (yo-) handles are shorter and heavier and have a shape that’s meant to mold to your hand; they can be made from plastic or wood. Japanese-style (wa-) handles are generally longer, lighter, and made from wood; they can have a more cylindrical, hexagonal, or even octagonal shape. One type isn’t better than the other; consult our full guide to knife handles to determine which is right for you.

- Weight: All the gyuto we tested are relatively lightweight, but some have a little more heft than others. The heavier the knife, the more power it has, allowing gravity to do more of the work when you slice. But heavier knives can fatigue your hand a bit more than lighter knives, which can feel especially effortless to wield.

- Spine Thickness: In general, gyuto have relatively thin spines, so they glide through food easily. Thicker spines can give the blade a little more downward power as you cut but can sometimes wedge into food a bit more and get stuck.

- For Lefties: Symmetrical Blades, Left-Handed Gyuto, or Smaller Asymmetry Ratios: Lefties will have the most success with gyuto that have symmetrical edge angles or are designed specifically for lefties. Failing that, lefties should generally look for standard (right-handed) gyuto with smaller asymmetry ratios of about 70/30 or 60/40; our lefty user testers usually found these easier to use. (They more frequently struggled with blades that had higher ratios of 80/20 and 90/10.) Some knife shops, including Korin, offer services to convert right-handed gyuto for lefties; one of our lefties confirmed that this made our co-winning gyuto by Masamoto even easier and more pleasant to use. As with any knife, we highly recommend trying before buying; this is the only failproof way to know that the knife you choose works well for you.

The Tests

- Slice tomatoes

- Dice onions

- Julienne peppers

- Brunoise carrots

- Slice greens

- Slice steaks

- Evaluate sharpness using industrial sharpness-testing machine at beginning and end of testing

How We Rated

- Sharpness: We rated the blades on how sharp they were and how well they retained their edge over the course of testing.

- Blade: We evaluated the design of the blade and how it contributed to the knife’s ability to cut foods evenly and precisely.

- Handle: We evaluated the design of the handle and how comfortable it was for hands of different sizes to hold and grip.

Buy at Korin

Buy at Korin

Buy at Chef Knives To Go

Buy at Chef Knives To Go