This delicious, golden, syrupy sweetener has been used as food and medicine in cultures around the world since it was first foraged more than 8,000 years ago. Today, honey is harvested worldwide by big corporations, your neighbors, and countless specialty producers. It can sweeten your tea, enhance both the flavor and consistency of your barbecue sauce, and bring out nuances in a hunk of blue cheese.

Most of us are familiar with the bear-shaped jars of honey, and you might even have one in your pantry right now. But there’s so much more to honey than that simple, sweet syrup. At its best, honey contains nuanced aromas and flavors. It can taste floral, bitter, acidic, sweet, and even have notes of menthol or tobacco. Like wine, olive oil, and oysters, honey’s flavor and aroma are impacted by its terroir. You get very different results based on where the honeybees live and work, including the honeybees’ diet, the time of the year the honey is harvested, and how it’s processed. Honey ranges in color from very pale yellow to dark amber. It can be thin and liquidy, thick and creamy, dense and viscous, or anywhere in between.

How Honey Is Made

Bees are industrious, intelligent, and collaborative insects. Forager bees fly miles a day gathering nectar from flowers and storing it in their second stomachs, called honey sacs. While collecting nectar, they also pick up pollen, which sticks to their hairy bodies. (This is how many plants reproduce, and why bees are essential to their life cycle.) The enzyme invertase, which is present in the bees’ honey sac, begins to break down the nectar. When they return to the hive they pass the nectar to worker bees who chew the honey, adding more enzymes, until the nectar is completely broken down.

The bees deposit the nectar into the hive’s honeycomb and use their wings to rapidly fan the honey until enough water has evaporated. During this process, the nectar transforms from a solution containing 80 percent water to honey, which contains 18 percent water or less. Once the honey has sufficiently dehydrated, the bees cap the honeycomb with beeswax, creating an airtight seal. This transformation results in the thick, luscious honey we know and love. The beekeepers leave the honey to ripen and mature, and eventually break the beeswax coating to release the honey from the honeycombs.

Processing Affects Honey’s Aroma, Flavor, and Consistency

Honey producers make a series of processing decisions that affect their honeys’ aroma, flavor, and consistency. Some producers value keeping their honey as raw and natural as possible, bringing it directly from the beehive to the jar without much intervention. However, most honey has at the very least been strained. Straining removes larger debris particles such as bee parts or pieces of beeswax.

Producers can go one step further and filter their honey once or several times to remove finer particles such as pollen. Filtration can slow down the process of crystallization, which extends its visual appeal for retail.

Honey heating entails a progressive browning and a more or less obvious loss of volatile substances that characterize the aroma.

Another processing decision is whether or not to heat the honey. High-heat processing kills any yeast that could cause off-flavors or fermentation, makes it easier to finely filter the honey, and dissolves any crystals, ensuring that honey stays liquid longer. But high-heat processing changes a honey’s aroma and flavor. “Honey heating entails a progressive browning and a more or less obvious loss of volatile substances that characterize the aroma,” writes Ettore Baglio in Chemistry and Technology of Honey Production (2018). Plus, high-heat processing reduces honey’s viscosity, thereby making it more runny.

Honey that has been filtered and/or heated will add requisite sweetness to tea or toast, but critics say it lacks the characteristics that make honey special, such as nuanced flavor, complex aroma, and viscous texture. Companies that don’t filter or high-heat process their honey typically note on the bottles that it’s unfiltered and/or raw. If honey is superclear, without impurities or imperfections, it’s likely been filtered at least once, and there’s a chance it’s been heated too.

Creamed Honey: Thick, Creamy, and Spreadable

Most honey is liquid, but you can also find thick, sticky honey with the consistency of lemon curd. This “creamed honey” is made by encouraging liquid honey to crystallize. Makers can either add a certain amount of already-crystallized honey to liquid honey or whip liquid honey, which adds small air bubbles for the crystals to grow on. In some cases, manufacturers use honey that is especially prone to crystallization.

Blended Honey versus Monofloral Honey

Many supermarket honeys are blends of several kinds of honey and as such are called polyfloral or blended honey. It’s common to see blends of wildflower honeys and blends of clover honeys. Often big brands will get honey from several sources across the country and sometimes from international beehives too. By blending the honey, companies ensure consistent flavor from year to year.

Monofloral honey is made when honeybees eat nectar from the same primary floral source; it typically contains between 20 and 60 percent nectar from that flower. Beekeepers can’t control bees’ flight patterns, but they can introduce them to environments when a specific flower is in bloom. To make “pure monofloral honey,” explained Francesca Paternoster, beekeeper and monofloral honey producer for Mieli Thun, “we look for specially selected, uncontaminated locations where we bring our bees in the peak blooming periods.” In the United States, there are more than 300 unique types of monofloral honey from different floral sources, according to the National Honey Board, and there are many more around the world. The flavors and colors of monofloral honeys can vary from season to season and year to year based on changes in environmental factors such as climate and rainfall. Honey harvested in the spring tends to be light in color and more delicate in flavor, while honey harvested in the fall is often dark and more robust, explained Mary Duane, president of the Massachusetts Beekeepers Association.

Adulterated Honey

Adulterated honey is honey to which another sweetener, such as corn syrup, has been added. Companies do this in order to cut costs and stretch their supply and also because the addition of corn syrup helps prevent crystallization. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has guidelines to clarify honey labeling so that consumers can make informed shopping decisions. A food cannot be labeled as simply “honey” if it contains another sweetener. If a honey contains corn syrup, it legally must be labeled as a “blend of honey and corn syrup.” If it contains more corn syrup than honey, it must be labeled “a blend of corn syrup and honey.” There are several home tests that purport to reveal whether honey is adulterated or not. However, the National Honey Board insists that the only way to know for sure is to test the honey in a lab.

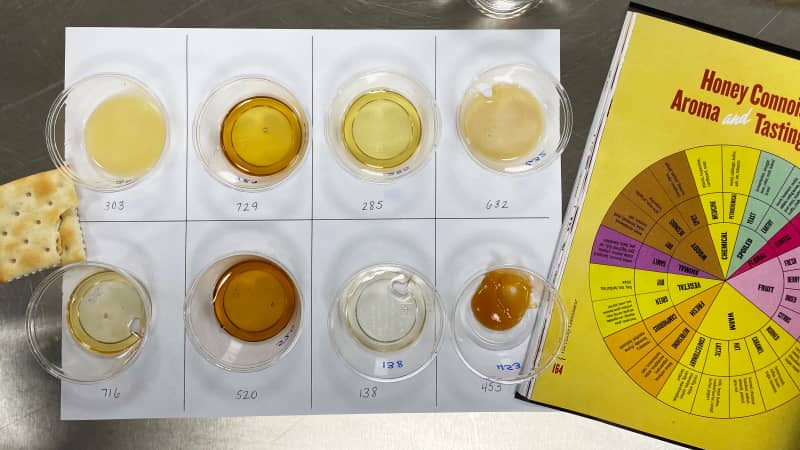

Our Honey Tasting

We set out to sample a broad array of honeys. We began by selecting the four top-selling nationally available brands of honey, according to Circana, a Chicago-based market research firm. We also consulted The Honey Connoisseur (2013) and spoke with Amina Harris, director of the UC Davis Honey and Pollination Center. Our final tasting lineup included several polyfloral blends, as well as nine monofloral honeys named for the flower source from which the bees primarily eat: acacia, blackberry, buckwheat, chestnut, linden, mānuka, meadowfoam, orange blossom, and tupelo.

Sampled plain, the blended honeys tasted “classic” and “familiar” with “sweet,” “fruity,” and “floral” notes. Some had a bit more nuance—“warm” with notes of “caramel,” “toffee,” and “brown sugar”—but none surprised our tasters.

The monofloral honeys, on the other hand, were a revelation, with complex flavor profiles determined by the flowers the bees visited. Honey made from the nectar of small meadowfoam flowers found near vernal pools in the Pacific Northwest, for example, had notes of “marshmallow” and “vanilla.” Honey made from tupelo trees that grow in the marshy environment on the border of Florida and Georgia was “earthy,” “musty,” “like wet wood or moss,” with subtleties of “citrus.” And honey made from Italian chestnut trees tasted “intense,” and “complex,” with “bitter,” “medicinal” notes.

Curious how they would perform in recipes, we baked Honey Cake with three types of honey—one top-selling blended honey, one monofloral acacia honey, and one creamed honey made primarily from clover and alfalfa. While the special flavor nuances of the acacia and creamed honeys were apparent to and very appreciated by some tasters, all of the cakes we made with the three types of honey were sweet and tender. For that reason, we think a majority of honeys we tasted, including less-expensive blended honeys, will work well when baking.

Which Honey Is Right for You?

Of the 15 honeys featured below, some are perfect for everyday use because they’re mild, sweet, and floral. Others are better for pairing with a cheese plate, mixing into homemade pasta filling, or drizzling over grilled meat. All have the characteristic sweetness of honey, but some might surprise you with their woodsy or even savory notes. Each is worth trying. Instead of ranking them, we’ve provided tasting notes and information about what the bees ate, where the honey was sourced, and how it was processed (when manufacturers were willing to disclose it). We’ve listed them below by style: blended honeys for everyday use first, monofloral honeys, and creamed honeys. Whether you’re already a lover of honey or new to the market, we hope our chart below imparts a new perspective of the wide world of honey.

- Taste honey plain

- Taste one everyday honey, one monofloral honey, and one creamed honey in Honey Cake

- Taste five honeys with cheeses, fruit, nuts, and bread

- Samples were randomized and assigned three-digit codes to prevent bias