You can make a lovely, eclectic cheese plate using only goat cheese. That’s how much this category of cheese varies. Logs of fresh chèvre are lemony and spreadable. Some styles of goat cheese age for several months and are much firmer and quite complex, the natural sweetness of the milk turned nutty and caramelly in flavor. And plenty of other goat cheeses, having aged just a week or two, exhibit a combination of textures. Their dry, crumbly centers are surrounded by delightfully gooey and delicate exteriors.

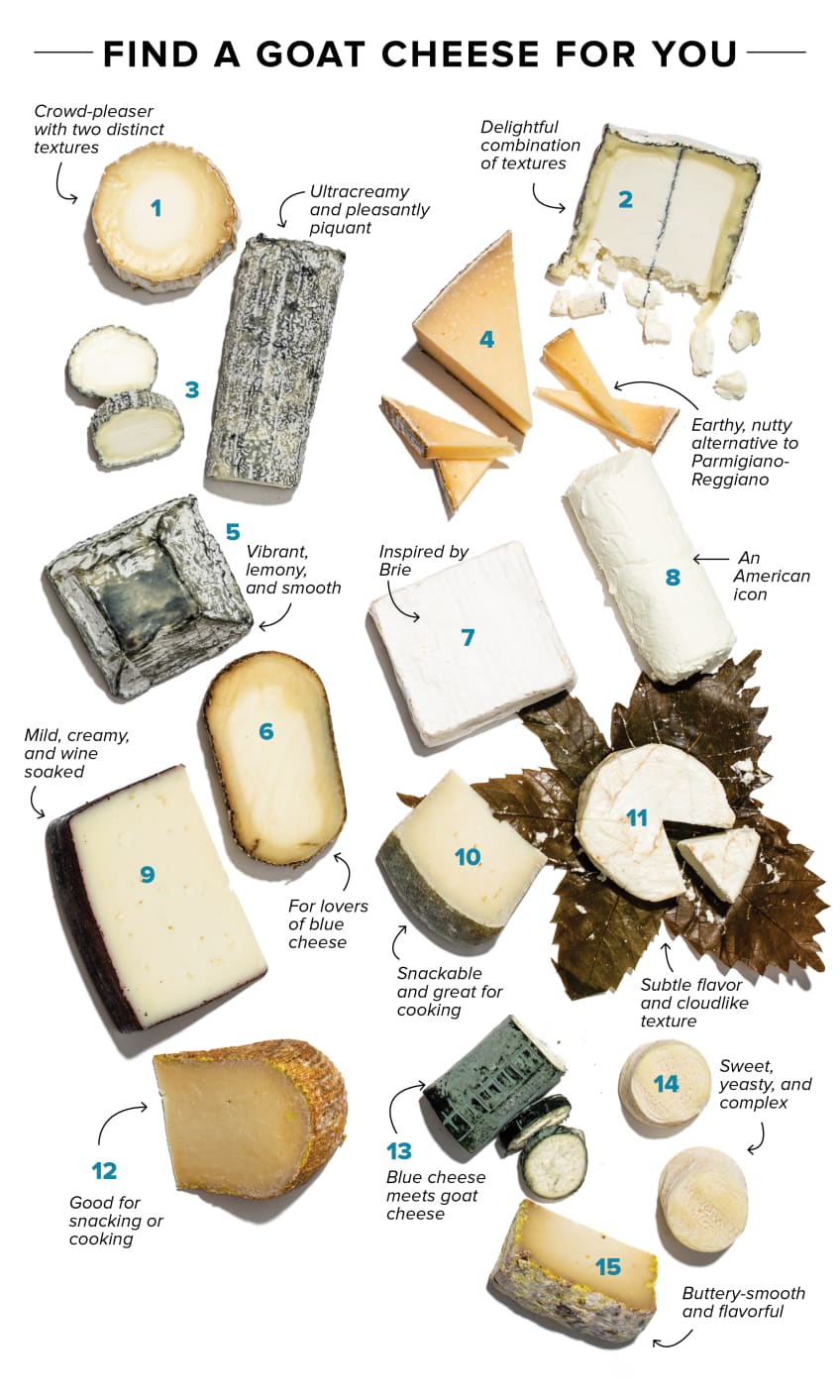

If the range of flavors and textures in goat cheeses comes as a surprise, you’re in excellent company. When I worked as a cheesemonger, many shoppers assumed that fresh chèvre was the only goat cheese around. Back then, I would cut samples from a few different goat cheeses and hand them over the counter. Now I have the opportunity to write about them. The goal is the same: to celebrate a broad category of cheese and help people find something they love. With input from experts, I put together a list of 15 goat cheeses. Nine are produced in the United States and six are made abroad. Some have been made for centuries, and two were introduced within the past few years. Two are fresh chèvres, while the rest have been aged for a period of several days or even several months. Each of these goat cheeses is excellent, and together they showcase the range of goat’s-milk cheeses available.

The Basics Of Making Cheese With Goat’s Milk

As with all cheese, the quality of the milk used to make it is of utmost importance. Among other things, it’s influenced by the breed of goat, the goats’ diets, and the time of year. Goat’s milk is also unique in color and composition. Due to how the animals process the orange-hued plant pigment beta-carotene, their milk is a brighter white than cow’s or sheep’s milk. The protein casein is distributed differently than in other milks, which may explain why some people with allergies to casein find goat’s milk easier to digest. Both things are also true of cheeses made with goat’s milk.

The milk used for most of the goat cheeses produced in the United States is pasteurized. (The U.S. Food and Drug Administration prohibits the sale of raw-milk cheese younger than 60 days, and few American goat cheeses are aged that long.) In France, where young raw-milk cheeses are common, cheesemakers often make pasteurized versions of their cheeses specifically for export. Valençay and Sainte-Maure de Touraine are two centuries-old French raw-milk cheeses that are available only in pasteurized form in the United States.

Whether the milk is raw or pasteurized, there are two main ways to turn it into cheese. Andy Johnson of the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s Center for Dairy Research explained that one method is adding acid to the milk, which gradually lowers its pH and causes the proteins in the milk to stick together. The other option is to add rennet, a blend of enzymes that quickly coagulates a type of protein in the milk and forms curds that eventually become cheese.

Making Fresh Goat Cheese

In France, “chèvre” means “goat” and “goat cheese” and can be used to refer to any cheese made with goat’s milk. In the United States, the term “chèvre” typically denotes fresh, spreadable cheese logs. After all, it was the first goat cheese to be produced on a commercial scale in the United States, and most cheesemakers who work with goat’s milk produce a chèvre. It makes up the majority of goat cheese in the United States.

It takes just three or four days to make and package fresh chèvre. Once formed, the loosely set curds are typically hung in cheesecloth to drain. Salt is added, and then the cheese is shaped into logs (or medallions) and vacuum-sealed. Because the cheese isn’t aged, it’s soft, rindless, and uniform in texture. The California creamery named for its founder Laura Chenel produces the most iconic chèvre—it first adorned the mixed greens salad at Berkeley’s Chez Panisse in the early 1980s, establishing American goat cheese as appealing and versatile and paving the way for many more makers and cheeses. Capriole, a pioneering creamery in Indiana, puts a spin on fresh goat cheese with its O’Banon. The curds are formed into disks that are later wrapped in bourbon-soaked chestnut leaves, which add a whisper of vanilla and oak to the bright, lemony cheese.

Aged Goat Cheese Essentials

Fresh goat cheese is a clearly defined style. Other goat cheeses—which come in any number of sizes, shapes, flavors, and textures—seem to defy categorization. The methods used to make them vary considerably by the style of cheese and the tools at the makers’ disposal. However, some of the broad strokes are the same. After draining, the curds are transferred to cheese forms that give the cheeses their shapes. (For some firmer cheeses, the curds may first be heated, or cooked, to further remove moisture.) The shapes range from petite rounds (known as “crottins”) or pyramids to wide logs and sizable rounds or squares. In the case of distinctive Humboldt Fog from Cypress Grove in California, the cheesemakers add a thin layer of decorative vegetable ash after half the curds are placed in the forms, forming a dark line that becomes visible when the cheese is cut. Some forms drain on their own, without any manual interference from cheesemakers. Others are pressed or stacked to remove additional moisture, with the weight of each cheese squeezing liquid from the one below it.

After the cheeses are removed from their forms, the aging or maturing process begins. Aged goat cheeses that mature for a relatively short period of time—often as little as two weeks—remain fairly soft and spreadable. It takes from three to five months to produce firmer, drier aged cheeses.

How Young Goat Cheeses Ripen And Mature

Cheeses that are aged for a relatively short period of time tend to be fairly delicate and have soft, powdery rinds. Many are made with Penicillium candidum, the same white mold used in the making of Brie or Camembert. Just like those familiar “bloomy-rind” cheeses, their exteriors are thin and downy. Geotrichum candidum, a mold-like yeast that produces soft and beautifully wrinkly rinds, is common in France and used to make many of Vermont Creamery’s and Capriole’s goat cheeses. Other goat cheeses have mottled dark-gray or even blue exteriors—and this causes a fair bit of confusion for shoppers. Some, including Valençay and Sainte-Maure de Touraine from France’s Loire Valley, are coated with the same type of vegetable ash that’s sprinkled in the middle of wheels of Humboldt Fog. The ash doesn’t add any flavor of its own. A select number of goat cheeses, including Spain’s Monte Enebro and the Classic Blue Log from Westfield Farm in Massachusetts, are coated with Penicillium roqueforti, the same mold used to make blue cheese, and boast a Roquefort-esque piquancy.

Any molds, yeasts, and bacteria applied to the surfaces of these cheeses also act on their interiors. You can see this very clearly as these fairly young cheeses age and continue to mature at retailers or in your refrigerator (see “An Unexpected Tip for Buying Soft Cheeses” for more info on how to find a young goat cheese with the age and texture you prefer). They begin fairly dense, firm, and uniform in texture. With time, the outer edges soften. A gooey, almost liquid band called a “creamline” forms and widens as it advances toward the center (or “paste”) of the cheese. The result is a cheese with two distinct textures in each wedge or slice. Cheesemakers dial in a multitude of variables, from the recipe and aging conditions to the size and shape of their cheese, with a target ratio of the two textures in mind. It’s rare for a cheese’s dense, fudgy center to be totally overtaken by the creamline.

Making Older, Firmer Goat Cheese

Goat cheeses that are aged longer—usually from three to five months—are firmer and drier than fresh or young goat cheeses. Cheesemakers deliberately add yeasts, molds, and bacteria to these cheeses as well, but these additives behave differently because they’re intended to work over a longer period of time. The rinds that form are harder. Even as they mature in both flavor and texture, these aged cheeses remain fairly uniform from edge to center. If anything, the outermost portion of the cheese is a bit drier and tastes a little more earthy.

The tommes—a fairly generic French term for aged wheels—produced by Blakesville Creamery in Wisconsin and Twig Farm in Vermont are good examples of rustic aged wheels. Other aged goat cheeses have slightly different exteriors. Washing (or rubbing) wheels with brine encourages the growth of bacteria that cause a rind to grow. Rachel, an aged cheese from White Lake Cheese in England, has a washed rind that becomes speckled with bits of orange mold. One Spanish cheese, The Drunken Goat, is submerged in red wine at least three times over the course of several weeks, which turns the exterior nearly purple and imparts a floral, fruity flavor.

The Big, Varied World Of Goat Cheese

Instead of a certain texture or technique, goat cheeses have an ingredient in common. Other than that, they are hard to categorize. The 15 cheeses highlighted here show the breadth of goat cheeses available. They range in size from tiny 2-ounce crottins to 5-pound wheels. Some become spectacularly soft and runny, with just a bit of the center still dense or dry. Others are always firm enough to slice or grate. All have the characteristic tangy sweetness of goat’s milk, but those flavors sing at different decibels. For every bright, zippy goat cheese there is another one with more subtle flavor.

Each one of these cheeses is worth trying, and it would be impossible to rank them. To help you find the ones—and I do hope there are many here that appeal to you—I’ve provided tasting notes and background information. Even if you regularly eat goat cheese, perhaps you’ll learn about a new cheese or have renewed appreciation for an old favorite.

- Taste 15 goat cheeses (six imports and nine made in the United States), priced from about $15 to about $62 per pound, purchased online

- Sample the goat cheeses plain, at room temperature

- Compare the goat cheeses’ flavors and textures